Peter Latta, A. Duie Pyle chairman and CEO, has turned down acquisition offers for the regional LTL carrier from two national competitors expanding into the Northeast in the past two years.

Instead, the West Chester, Pennsylvania-based carrier marked its centennial this year as a private, family-owned business, hosting harbor cruises and other celebrations for its workforce of 4,300 employees.

“We're absolutely committed to the Pyle people and remaining a family business,” Latta told Trucking Dive in an interview. “We've gotten through the first 100 hard years, and now we have the next 100 hard years to get through.”

Pyle’s growing operations reach from the Canadian border in Maine to the Virginia-North Carolina line, and westward to West Virginia and Ohio. The carrier, which interlines with Dayton Freight Lines and Southeastern Freight Lines, earned $775 million in revenue last year.

Starting with two trucks — and operating a single terminal until 1996 — Pyle survived labor unrest and other disruptions that sent its competitors out of business over the past century by fostering and sustaining a culture of trust among the owners and workforce, Latta said.

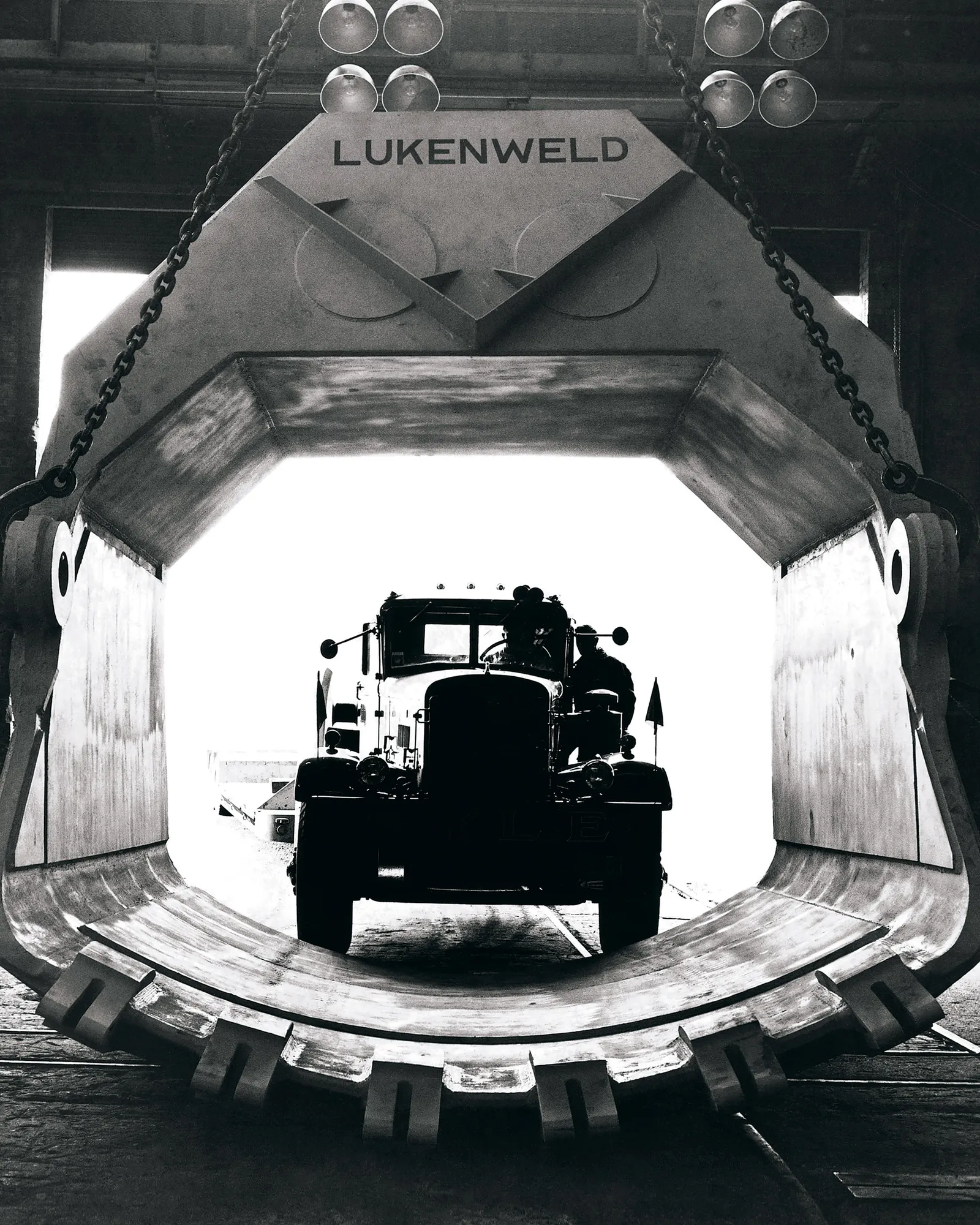

Pyle’s first customer, Lukens Steel, is a testament to Pyle’s place in Pennsylvania’s trucking history, which witnessed trucks hauling steel, coal and food to support industrial and population growth, said Rebecca Oyler, Pennsylvania Motor Truck Association president and CEO.

“The history of our nation in the 20th century is so intertwined with the history of trucking in Pennsylvania, and A. Duie Pyle should be proud to be a big part of that story,” Oyler said in an email.

‘Not just a number or a body in a seat’

Jesse Weeks commended Pyle’s approach to its workers as he pulled a 40-foot trailer with shipments of paint, coffee, motorcycles and more from a terminal in Jessup, Maryland, around the Baltimore area one day in May.

The 48-year-old Pyle driver has driven trucks for 27 years, and he was the carrier’s first hire when it expanded into the Baltimore area, he said. Now, he trains other drivers.

Executives greet Weeks and his fellow drivers by name. They visit terminals regularly to meet with drivers over meals and collect feedback.

“The owners know you,” Weeks said. “You’re not just a number or a body in a seat.”

Pyle leaders reinforce that trust by telling their workforce about acquisition offers — as well as their reasoning for rejecting them.

“The common comment [from] a lot of companies that acquire is, ‘Nothing's going to change,’” Latta said. “Well, everything's going to change.”

Publicly owned carriers, such as the pair of freight giants that failed alongside private equity firms to acquire Pyle, live and die by quarterly earnings results and analysts’ opinions, Latta said.

“We don’t want to be in a fishbowl,” the chairman and CEO said. “We are very open with our people — because we're absolutely committed.”

‘How did we survive?’

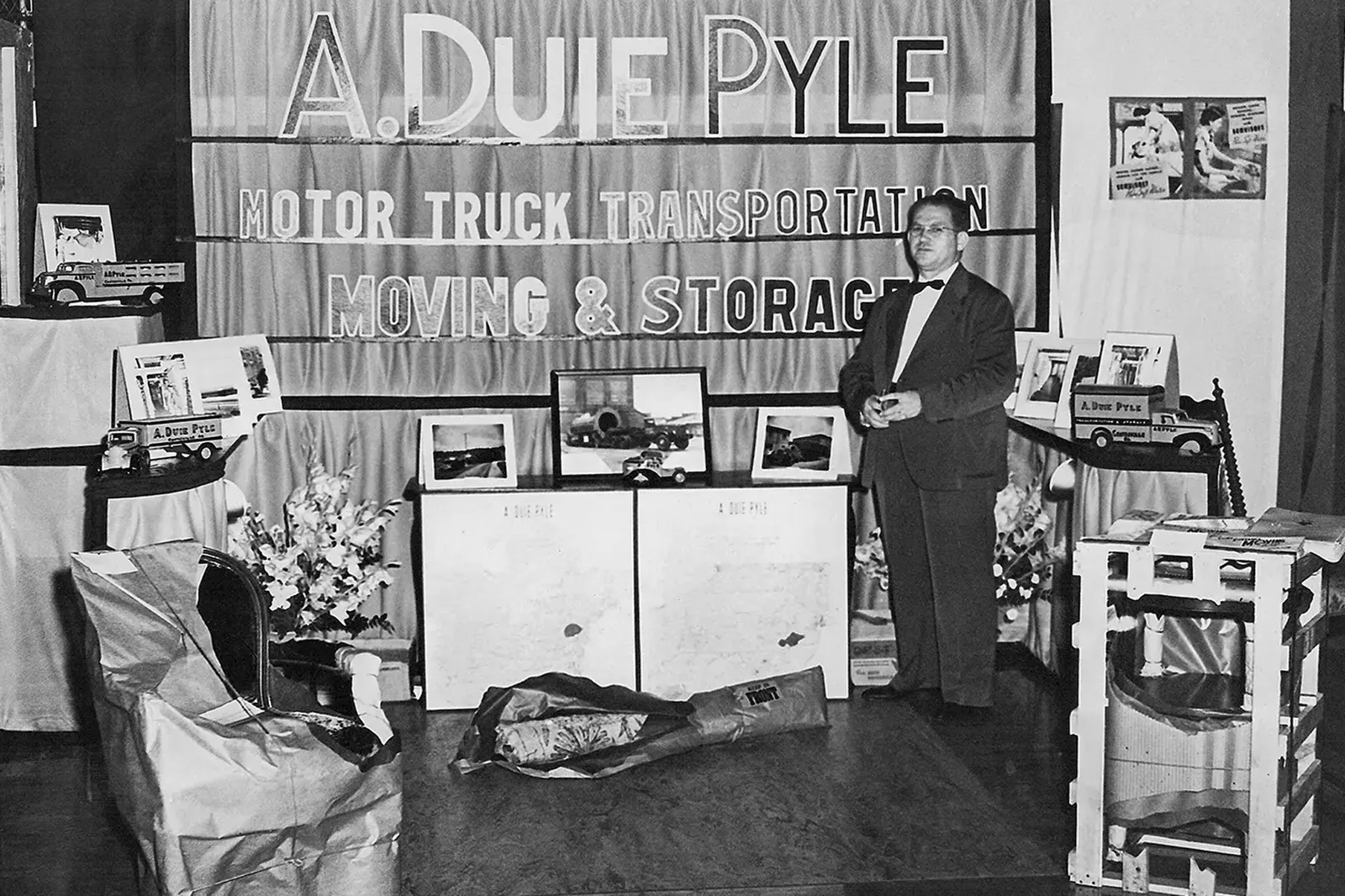

Founded on April 1, 1924 with a used 1918 International Harvester truck by Alexander Duie and Mary Ellen Pyle, the company has grown alongside its customers into a premier regional carrier.

Making it to 100 years required surmounting a litany of challenges, including the Great Depression, World War II, a 14-week strike, deregulation, a ransomware attack, the COVID-19 pandemic and a roof collapse after a snowstorm at a West Chester facility.

“We had two warehouses, one terminal and less than 100 people on the team. How did we survive when the carriers that had the market, the customers, the facilities, they didn't survive?” Latta said. “I attribute it to a three-word answer, and that's: ‘the Pyle people.’”

The strength of the company’s relationship with its workers stood out to Latta in 1979 as he watched striking workers decide to leave the Teamsters union and end the strike.

“It was a very different Teamsters world in those days than it is today,” Latta said. “They took a lot of risk in crossing that picket line, and saying to the union, ‘No more. We're done.’ That taught me a lot about trust and the power of it.”

Jeff Young, a 62-year-old Pyle driver who goes by the nickname “Squeak,” said the culture was evident in his job interviews 30 years ago with Latta and his father, Jim Latta, who remained involved after passing the torch.

“As long as you work hard, and tell the truth, and do a good job for us,” Young recalls Jim Latta telling him, “you’ll always have a job here.”

As CEO, Peter Latta has served as “such a good steward of the company” and overseen its growth, said Jim Craig, the Jessup terminal manager.

Taking care of ‘the ones who make the wheels turn’

Beyond the harbor cruises and truck-themed cake, Pyle’s centennial celebrations have also featured the commissioning of a model of the company’s original 1918 International Harvester.

Pyle workers have been at the center of the festivities. They were the ones, after all, who immediately got to work shoveling snow after the roof collapse and sustained its operations each day, including through the June 2019 ransomware attack and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Weeks is looking forward to a party Pyle is throwing this fall at the National Aquarium in Baltimore for its employees in the area.

He enjoys his job and feels that Pyle’s leadership understands “we’re the ones who make the wheels turn,” so “they’re the ones who make sure we’re taken care of.”

Hauling freight has allowed the driver to raise two sons, Peyton, 20, and Trenton, 17, in Mount Airy, Maryland.

“It’s afforded my boys to have a good life,” Weeks said. “I can provide them things they want and need because of my willingness to come out and work.”

Pyle believes its investments in its people and technology will be key to its future success as it adds four terminals it acquired from Yellow Corp., which went bankrupt just shy of its own centennial last year.

“Cultural engagement and discretionary effort — it's important to capitalize on opportunities,” Latta said.

Visuals Editor Shaun Lucas contributed to this story.